a.k.a. the moment of change is the only poem

Driving to the limits

of the city of words…

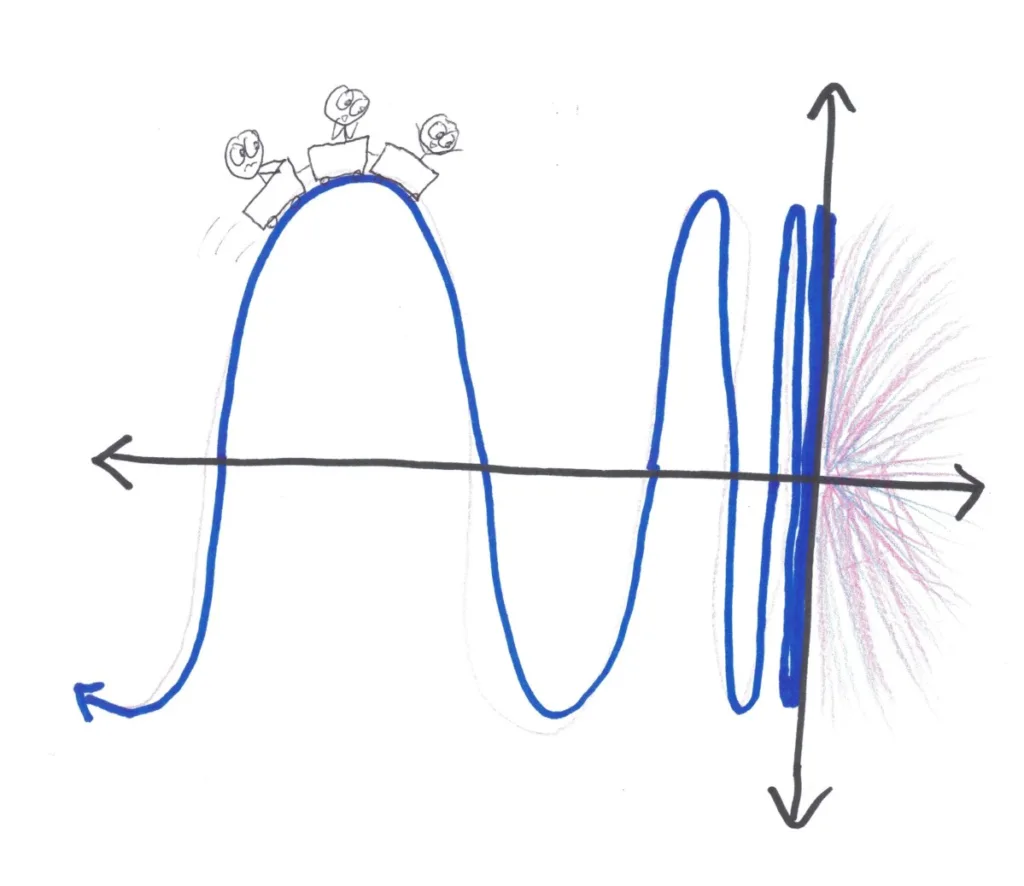

Before we get to Adrienne Rich, feminist poet/mathematical analyst, let me begin with a gripe. As a calculus teacher, I’ve never loved the word “limit.”

“Limit,” to me, gives entirely the wrong impression. A “limit” is a fence, a boundary, fixed and non-negotiable. But we’ve pinned this rigid name on one of our most dynamic and enigmatic concepts: the impossible end of an infinite process, the day after eternity.

Instead of limit, perhaps we should say destination. Or perhaps we could commission ultimate as a noun. (Imagine Lindsay Lohan’s cry: “the ultimate does not exist!”)

But really, I wish I could ask Adrienne Rich what to call it. She’d know.

In 2017, when I was writing my book on calculus, I fell deep into Rich’s poetry. Calculus sets geometry and algebra in motion; it is a leap from the static to dynamic. That’s precisely the sort of leap that Rich’s poems bring to life.

Indeed, it’s precisely the leap that she lived herself.

As late as 1959, the young Rich was living a life of conventional respectability. Three kids. Nice house. Harvard professor husband. She wrote poetry to match: artfully crafted, steeped in tradition. As she would later describe it, this was static poetry for a static life.

But soon, Rich began a transformation. The first changes were small. For example, she started dating each of her poems by year:

I did this because I was finished with the idea of a poem as a single, encapsulated event, a work of art complete in itself; I knew my life was changing, my work was changing, and I needed to indicate to readers my sense of being engaged in a long, continuing process.

Gradually, she came to reject her early writing (and her earlier lifestyle) altogether. “I [had] felt,” she explained, “as many people still feel—that a poem was an arrangement of ideas and feelings, predetermined, and it said what I had already decided it should say.”

She began to see poetry instead “as a kind of action, probing, burning…” She ditched the well-mannered verse and began to experiment. Colloquial rhythms. Streams of consciousness. Raw intimacy. “Instead of poems about experiences,” she wrote, “I am getting poems that are experiences.”

Dynamic poetry for a dynamic world.

This math-to-feminist-poetry connection might not seem obvious, or, for that matter, entirely respectful of Rich’s depth. But I’m hopeful that Rich herself would have embraced it. Though she devoted her life to poetry and politics, she saw a crucial role for the quantitative, too. “We might hope to find the three activities—poetry, science, politics—triangulated,” she wrote, “with extraordinary electrical exchanges moving from each to each.”

As a case study, take 1971’s “Images for Godard,” a tribute to the French director. Rich writes:

the poet is at the movies

dreaming the film-maker’s dream but differently

We could dig deep into that line, and its insight about the static, the dynamic, and the nature of art. But I want to leap ahead to the final section of the poem, which begins:

Interior monologue of the poet:

the notes for the poem are the only poem

What Rich is saying–or what I hear her saying–is that the final draft of the poem itself is never as true or as beautiful as the initial notes you make for it. The printed thing lacks the spontaneity, the freshness, of those first notes.

But then, just a few lines later, she modifies this thought, refining the initial meaning, nudging us deeper:

the mind of the poet is the only poem

Ah, so it’s not the notes themselves. It’s the frame of mind in which the poet wrote those notes. It’s the inner experience.

But then, Rich revisits this thought a third time, ending the poem with one of the most famous lines she ever wrote, one that I clumsily borrowed as an epigraph for my calculus book:

the moment of change is the only poem

What is she saying?

Well, I don’t think she’s “saying” anything at all. Rather, she’s showing that a poem’s meaning can’t quite be fixed into place, or spelled out, or forced to stand still. The meaning of a poem isn’t localized in any specific word or particular phrase.

The meaning is found in the flow—the dynamism—itself.

As a poet, you know you’ll never quite reach the inexpressible core of truth. But with ingenuity and dynamic language, you can approach that deeper reality, closer and closer and closer…

The truth is the thought approached, not the words we use to approach it.

It is what mathematicians call the “limit”—but as I’m sure Rich would tell you, that word is not quite the whole truth. No word ever is.

Published